Hollister- "A drinking club with a motorcycle problem."

Yes, i am once again tracking down ALL the stories, all the truths-- all the bits and pieces of a story that has caught my imagination and shaken it like a pit bull with a baby.

Here is the basic:Screenplay from the short story, "The Cyclists' Raid" by Frank Rooney, in turn based the article, "Hollister Riot", which featured prominently

in the July 1947 issue of 'Life' magazine.

http://www.onehellofaneye.com/2011/06/03/

One Hell of An Eye

The Official Blog of Mike Salisbury

Secrets of Dreams, Part I

“There was a myth before the myth began,

Venerable and articulate and complete.”

–Wallace Stevens

The Happening

“This bike has a story,” said the kid in the jeans with a big cuff rolled up over his old school engineer boots as he pushed the

Yes, i am once again tracking down ALL the stories, all the truths-- all the bits and pieces of a story that has caught my imagination and shaken it like a pit bull with a baby.

Here is the basic:Screenplay from the short story, "The Cyclists' Raid" by Frank Rooney, in turn based the article, "Hollister Riot", which featured prominently

in the July 1947 issue of 'Life' magazine.

http://www.onehellofaneye.com/2011/06/03/

One Hell of An Eye

The Official Blog of Mike Salisbury

Secrets of Dreams, Part I

“There was a myth before the myth began,

Venerable and articulate and complete.”

–Wallace Stevens

The Happening

“This bike has a story,” said the kid in the jeans with a big cuff rolled up over his old school engineer boots as he pushed the

black motorcycle across the dock into the back of the pickup.

“What’s the story?” I asked.

“Dunno,” the kid said. “It’s the bike in that really cool poster back in the showroom. It’s famous.”

“The really cool poster of the guy in the leather jacket and the hat with the motorcycle?” I went into the showroom to take a look at the poster. I know it well. The black and white photograph of Marlon Brando leaning on the tank of a motorcycle with a trophy tied upright to the top of the headlight. A cap is cocked to one side of his head showing a black sideburn on the other side. Johnny is lettered in script on his black jacket. The bike is a 1950 6T Triumph Thunderbird. Its name is in front of Johnny’s on the most indelible motorcycle image ever. The Wild One.

The first motorcycle cool. Even the kid on the dock wore the jeans rolled up like Johnny.

“Hollywood bullshit.” Turning around, I see a bandanna of a very different color covering most of the grey on long black hair. President is stitched in the same color on the sleeveless jean jacket. Under the jean jacket is black leather. “The movie is supposed to be a real story. But it ain’t,” the graying biker said. “Never happened.”

“What never happened?” I asked.

“Hollister,” the biker answered. “There was no riot and no bad bikers in leather jackets with caps like that either. And that actor guy never rode a motorcycle.”

I stumbled on the words as the graying biker turned and walked away. On the back of the faded blue denim, a seriously bad biker gang’s ID is embroidered in gothic lettering on a patch of that color.

I shut up.

What is the story of this bike that had a trophy on the fender and its name in front of Johnny’s? Was it just a Hollywood invention? Whose? Who dreamed Johnny Strabler, the motorcycle rebel in the cocked grey cap on that poster? Johnny, with his name on the most notorious jacket in history? A jacket the cops of New York City would be banned from wearing.

And Hollister? What was this Hollister all about?

I pulled the phone out of my Levis and punched in a 323 area code and telephone number. “Harvey around?” I ask. I pause. “Harv? Found you. The Wild One. If anybody knows about movies and icons and motorcycles it’s you. What is the story?” I paused. “Brando’s look. Where did it come from? The jacket. The hat and boots. The jeans.” I listen. “Why the Triumph?” I go on. “What was Hollister really all about?” I pause again. “Was the movie that brought them together –that motorcycle, that jacket and Hollister —really just a Hollywood dream? All phony?” I pause, “Ok. Thanks. See you there.” I stick the phone back in my jeans, zip up the black jacket.

The front wheel of the Triumph lifts in spinning slow motion at the bottom of the Santa Monica Incline. Turning north, it drops at an angle onto Pacific Coast Highway in front of the black motorcycle. I am on the road back through time to the secrets. Secrets of invented dreams. On a black motorcycle, like Johnny. In black leather like him. To find Johnny, The Wild One. To find secrets of black leather and chrome dreams. Hollister and Hollywood .

Faded mansions of dead movie stars that hide the beach on the clutch lever side become a streaky Painted Desert wall of sand colored stripes. I am over the posted speed limit. What are you rebelling against, Johnny?

“Who created the famous line of Johnny’s?” I ask myself.

Blue sea glitters hot where the houses end at the Santa Monica city limit. Arid cliffs a quarter mile high on the right fall straight and fast to the highway. Halfway up the dirt walls, dry scabs of pastel plaster are crucified on the thorns of the cactus that will always survive. Bits of a cardboard dream hanging in the air above the abrupt western dead end of L.A. Someone invented a place they called home on an overpriced unnatural lawn at the top of this naked dirt. The unreal house that nobody ever wanted to believe would fall down the cliffs, fell. Down to the highway where the sun sets on the secrets of Hollywood dreams.

Johnny’s look –the black leather jacket, the cap — may be the most copied clothing in the history of world popular culture…where did Johnny come from?

Leaning my left knee into the tank, I push the bike to the right. The bike’s slow moving front end feeds back the news that that the ends of the turn have more ripples than a Sumo wrestler’s ass so I hammer it up Sunset Boulevard.

What really happened July 6, 1947– what the San Francisco Chronicle called the worst 40 hours in the history of a town?

I have a meeting in Hollywood to find out. First stop back to the future of motorcycle cool. The story of Hollister.

Harvey Keith, writer, director, actor, is standing over the bar guarding straight Chopin in a martini glass like a cat overseeing a goldfish bowl. “Of the 57 people listed as cast and crew of The Wild One, three are still alive and Brando apparently ain’t talking anymore,” Harvey said smiling. “I’m in the DGA and the Writers Guild and SAG…I called ‘em all for you. And I sat out the Vietnam War getting shot as a New York City cop, so I got that kinda records access too.”

His black leather sport coat is hanging on the back of the barstool behind him. Black muscle-tee, black slacks, the shoes are black and thick silver chains are stacked on his wrists. Tattoos have faded into hard biceps twisted with age like anchor rope for a tanker. “You know I was in a motorcycle gang too,” he says. “In Brooklyn.”

“That’s why I’m here,” I said.

“We took our whole thing from The Wild One. We looked bad. The movie was banned in England, that’s how bad we thought it was. We rode Harleys.”

“Why not a Triumph like Brando?” I asked.

“Sonny Barger [founding member of the Oakland chapter of the Hells Angels] said he liked The Wild One too. But he cheered for Chino–Lee Marvin–the bad guy.” Harvey answers. “Brando was the good bad guy, he had a Triumph. The bad guys had Harleys. We thought we were bad. We did wear black jackets like Brando. No way did we wear that Village People hat.”

“Was any of it for real?” I asked. “The Wild One. The leather. The bikes. Bad bikers. What is the story?”

“In 1947, Fourth of July,” Harvey said, “the AMA held a motorcycle race in Hollister, California. Just a race. Sportsmen. But bikers came in from L.A., from San Francisco, all over, to party.”

“A riot?” I asked.

“According to the papers from back then,” Harvey replied. “4,000 people got a little more than out of hand. Life magazine took a shot for the cover of a guy lying on a bike with a beer bottle in his hand. The street around the motorcycle was covered with beer bottles. The main street of Hollister. The AMA freaked out. That is where the one percenter came from. The AMA said that was not a true picture. The percentage of bad bikers was only “one percent” of all the motorcyclists. Then Frank Rooney wrote a piece in Harpers called “Cyclists’ Raid” that he said was based on Hollister. That became the screenplay for The Wild One.”

“With biker gangs tearing up the town.” I said. “But, Harvey, everyone now says the thing was blown way out of proportion. Even people who lived there said in interviews that these were all good boys back from the war just having a little fun spending some money in the community.”

Even the youth market; for Mattel by M.S.

“Bullshit,” Harvey comes back. “How can you make that shit up? Jerks who never rode a bike and presume to be intellectuals also say that motorcycles were just cheap transportation after the war, nothing more. An alternative to the overpriced used cars that were hawked on TV by Mad Man Muntz. That the guys who rode were displaced youth–alienated after the war, innocents confused, choosing a free life on the road instead of settling down to a slow middle class death in a grey flannel suit. The police reports from Hollister say different.” Harvey went on. “There was a lot of shit that happened in Hollister that had nothing to do with being confused about whether or not the bikers should live in Levittown. ‘Let’s just fuck over Hicktown!’”

“And motorcycles were the best horses for that Apocalypse. ” continued Harvey. “Wino Willie Folkner [Founder of the Boozefighters Motorcycle Club and rumored to be the model for Brando in The Wild One] was interviewed in the L.A. Times just before he died. He said different. He should know. He was there. One of the last L.A. Boozefighters.”

“Boozefighters?” I asked.

“Sound like the name of a good little boys club?’ Harvey laughed. “Having hung around bad guys on bikes, I can tell you that some guys were bad before Hollywood ever dreamed of ‘em. I don’t think the Hell’s Angels are a halfway house for case studies of misguided youth rebelling against the constraints of a square society. The Boozefighters became the Hell’s Angels. Willie said they went to Hollister to drink. A lot. To fight. He said they got drunk and drug a guy behind a car. Tipped over a police car. Rode bikes into bars. Tried busting other bikers out of jail. Basically all the stuff that the ‘Cyclists’ Raid’ is about and a lot of the stuff that is in The Wild One.”

“As an ex-cop, that shit seems kinda felonious to me,” Harvey said. “At the least, by today’s standards I see a few D.U.I s there. In his biography, Stanley Kramer – the producer of the movie – says that real bikers gave them the lines ‘…whatta ya got…’ and ‘…we just go…’ Confused, my ass…like I said, you don’t make this stuff up. Cheap transportation..right! Dude, everyone at Hollister was riding choppers and bob jobs, that ain’t cheap wheels. That’s a statement. And if they were all really so fucking naïve and sweet, how come you had to buy a Honda to meet the nicest people?”

“Even some tough old biker guy in gang colors told me it was all crap this riot stuff, the bad motorcyclist at Hollister,” I said.

“Weird.” Harvey said.

“Why?” I asked.”

“Because why would a one percenter, a guy whose reputation depends on creating bad news about motorcycles, why would he not want to be a part of the first bad news about bikers–Hollister?” said Harvey.

“But that still doesn’t answer the question about why there’s so much divided opinion about what really happened there,” I persisted.

“Who conceived the jacket and the hat and the boots for The Wild One?”

“There is no costume designer or wardrobe listed in the credits for the movie,” I answered.

“I know a guy who collects motorcycle jackets; you can find him Sunday morning at the Rock Store,” Harvey said. “I told him you would be there. He has the answer.”

To be continued….

Thanks to Patrick Cook; Mark Brady, Todd Andersen & Monika Boutwell; Peter Jones and Harvey Keith.

The Look

“He’s a rebel and he’ll never ever be – any good

He’s a rebel ‘cos he never ever does – what he should

And just because he doesn’t do what – everybody else does

He’s a rebel…”

Wouwch! Shotgun exhausts crack my eardrums like 50mm cannons fired in a storm drain. Gears are found down low to slow a mysterious train. Motorcycles. Leather. 15 maybe 20. Harleys mostly. Snaking north along the Pacific Ocean passing me on the Triumph by the lifeguard station where Pam Anderson jiggled her invented plastic dreams into the sharply focused eyeballs of families around the world.

The pack snaps over hard starboard, ducking out of the sun into tunnels of oaks at the bottoms of narrow canyons. The road to the Rock Store. Like Alice after the White Rabbit, the Triumph easily falls in line, hanging back unseen in the shade of the ferns creeping cautiously over the edge of the corkscrewing blacktop. Under the tires, the ice of the last cold mornings is slowly melting.

Kathy: “I’ve never ridden on a motorcycle before.

It’s fast. It scared me, but I forgot everything, it felt good.

Is that what you do?’’

A long chrome Slinky with more than 6,000 cubic inches of two-piston power bends around 359 degree turns–barely the radius of a schoolyard merry-go-round. Not one darkened brake light turns red. Up into the cloudless blue of the sky sitting on the treetops. Up almost a mile, the road flattens to horizontal between twin rows of naked pink rock. On top of this skinny mountain that cradles a wide valley big enough to hide Manhattan, in front of Ronald Reagan’s old ranch just outside of normal America, more motorcycles. Five-figure sport bikes, cruisers handmade of unpolished iron crosses, a stretched candy apple custom with a ‘57 Chevy rear end, purple painted faux leopard skin covered hooligan bikes, a jet powered cycle and a milk crate hard wired to the remains of a rotting chrome fender stuck to some kind of charred frame. All rumble, roar, hiss, whine and puff two wheels at a time onto the parking strip below the store made out of rocks. A small city of metal and leather on a narrow splatter of asphalt that is melting in the heat of the dry sun. A lot of bikes. Mostly cruisers. The biggest part of the motorcycle market. All in black leather jackets like The Wild One. I recalled that in his autobiography, Charles Mingus tells a secret – that he invented himself in a dream. But who invented Johnny?

Johnny: “We jus’ go.”

No one cares that they don’t sell rocks at the Rock Store. The Santana wind blowing hot from the east, whipping the trees beside the road, violently shoves the erratic painful noise of the eternal parade of motorcycles through the wall of heat rising from the barely two lanes of broken blacktop. Stopping the wind across the road on this ridge of mountains running above Pacific Coast Highway from the 24/7 of L.A. north to the strawberry fields of Ventura County, is the Rock Store. A café of the greasy spoon persuasion is on the south side, married to the store –a half empty gift shop– uphill on the north with a busy outdoor saloon and barbecue pit on the hill rising up from both. All made of big round rocks.

I don’t know which is Vern or which is Ed, but they own the place and open it only Saturday and Sunday. In front of the buildings stretching about a football field distance in both directions is a wall of motorcycles parked facing the road. Choppers and hogs are always on the right side in the shade under the only trees near the store. A pair of dead old gas pumps rusts in the heat of the naked sun on the narrow parking level below the café to the left of the cruisers. The pumps are always buried in tricked out sport bikes and exotic European collectible hardware. Japanese with video cameras are usually in there somewhere and Jay Leno usually shows up to pose beside the pumps for them. Jay sometimes drives one of his weirder old cars or sometimes bikes here. He is fast enough on the corkscrew road to the store to have passed my jailable speed on his Buell.

Sometimes lines of exotic cars on some kind of poser rally pass by the store. They gawk at the bikes. The bikers don’t really pay much attention to any cars. In a city built on cars like L.A., there aren’t really any as exclusively cool as a motorcycle anymore and the Rock Store is the Big Rock Candy Mountain of Cool. You can see fit-as-a-yoga-instructor baby boomer babes in conchoed vests and chaps with nothing under them but tan skin hanging with bearded outlaws in top hats and chains on the cruiser side. Segregating themselves on the sporting side, are the young and restless in skintight full racing suits. And it’s all wrapped in leather, including Jay.

Boyd Elder is an artist. He lives somewhere in Texas just south of nowhere close to ZZ Top. “Where did Brando’s Wild One outfit come from? Harvey said to ask me, right?” Boyd launched.

Never-washed tailored black Levis are slit to fit Boyd’s Lucchese boots custom made from some kind of endangered small black animal. Over the temples of prescription lens Persols he slicks his hair back behind his ears and down to the top of his collar. He has on a short sleeve black shirt with orange and red little flames all over it that he designed. Under a black leather jacket.

“Thanks man, for coming.” I said.

A large black envelope shows under Boyd’s arm as he raises his hands to light up an American Spirit. The label on the envelope is printed with one of his pinstriped steer skulls from the cover of an Eagles album. “I have customized cars, built hot rods, made a motorcycle from pistons and parts found buried under chickenshit, “ Boyd said. “And I wore that jacket and jeans with the big cuffs over those boots when I rode it.”

Boyd casually flips his unused cigarette into a long glide across the blacktop and drawls, “I collect old motorcycle jackets, you know,” he continues. “And I have pictures of every damn person with that look. The Beatles, The Ramones, Francesco Scavullo, Mel Gibson, Bruce Springsteen, Freddie Mercury, Jean Paul Gaultier, Madonna, Dolce Gabbana, Britney Spears and more queens of Halloween parties than you could find in the complete works of Tom of Finland.”

“And Brando first had the look back in 1954?” I ask.

“Well, yes and no.” Boyd opened the black envelope. He puts one knee on the asphalt and lays out photos backside up and like a blackjack dealer, flips over one to show its face. “Hollister. 1947,” he says. “Before somebody named Perfecto designed the One Star for Schott.”

It is an old photo. A western town. A mess of gals and guys hanging out under the verandas of the shops on the high walk.

In the front of the photo is an Indian bob job. The front fender is gone with most of the rear one. Standing just behind the Springer front end holding a longneck bottle at the end of a striped sleeve is someone wearing the sweater Lee Marvin wore in the movie.

“The same bumble bee striped jersey Columbia Pictures sort of donated to Frisco Frank of the San Francisco Angels after Frank convinced the studio that was the charitable thing to do,” said Boyd. “He wore it every day until it turned to dust.”

“Then Chino was no Hollywood dream,” I said. “Was Brando?”

Boyd points to the rider on the Scout in the picture. He is turned to the crowd while reaching out to the ape hangers. His arms in sleeves of black.

“Johnny’s black leather jacket.” I said.

“In the late forties Buco had the design and so did Indian.” Boyd said.

The guy in the old photo is wearing not just the jacket, he has the engineer boots too. A suicide shifter is sticking out from under the right leg of faded jeans rolled up to show about 8 inches of cuff. “Everything Johnny wore. Everything.” said Boyd.

“Everything except that cap?”

Watching my eyes, Boyd sees that question. He flips over another glossy. In the center of the photo, cocked at the same angle as Johnny’s in that poster with the trophy and the Triumph. Right on top of Manfred von Richtofen’s Teutonic head, is that cap. “The Red Baron,” Boyd said. “His Luftwaffe cap. And look at the lapels on this coat of his.”

“The One Star? But it’s an overcoat.” I said.

Boyd turns over another shot of von Richtofen. “He cut his off. To be cooler than the others when they went partying after a hard day of dogfightin’. Like a Catholic schoolgirl does to her uniform skirt. Shit, man,” he mutters out of the corner of his mouth as he fires up another smoke. “The Red Baron was the baddest. His look had to be cool.”

“It makes sense for motorcyclists,” I argued defensively, “because of the protection against the cold. It won’t tear like cloth and you slide in leather. You don’t get stuck on the asphalt waiting for an Acme semi to flatten you like The Roadrunner.”

“Nice try.” Boyd smirks. Opening a black hardcover book he says: “Mick Farren writes in his book The Black Leather Jacket that it is just better protection against knives, brass knuckles, chains and straight edge razors. Mick says that juvenile delinquents adopted the jacket as their own, as did the local police department, but first the Nazis firmly cemented the relationship between menace and black.

“You don’t make this shit up, dude,” said Boyd.

“Hollister happen?” I ask.

“Dunno,” he said.

“So who put it all together? “ I asked. “Who created Johnny’s look?

“Dunno,” said Boyd again. “But I’m getting the feeling of impending entrapment by the morals police with all this salacious talk of men in leather,” he laughed. “Had Hollister not happened, had Life magazine not written their article, had Hollywood not glorified it, I don’t know if we would be here today.”

‘An old boy from Oklahoma, Whitey Hughes.” said Boyd. “You can find him in Chatsworth,” Boyd said as he tore off a part of the American Spirit pack and wrote Whitey’s phone number on it. “He knows.”

Thanks to Patrick Cook ; Mark Brady, Todd Andersen & Monika Boutwell ; Peter Jones, Harvey Keith, and Boyd Elder.

…to be continued…

THE MOTORCYCLE

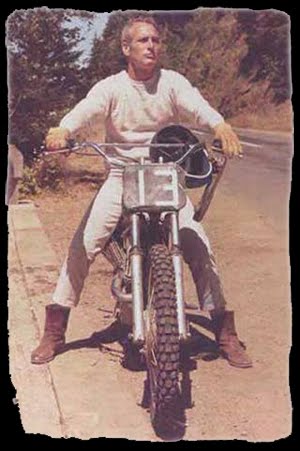

Steve McQueen's pickup.

“…the motorcycle came to function both as an object of desire

and a symbol of unrestrained Eros.”

–Art Simon, The Art of The Motorcycle

–continued: The city of Los Angeles is a punchbowl rimmed by the San Gabriel Mountains. The home of the Lakers is at the virtual center in the bottom. From Hollywood at the upper left end of this basin, the Santa Monica Mountains take over and run about 30 miles north to the L.A. county line. Leaving the Rock Store, on top of the part of the Santa Monica range that didn’t slide into the ocean in the mud of winter storms or get burned down in the late summer fires, the road is rougher than Godzilla’s complexion, but for a little piece of plastic-covered foam no bigger than Arnold’s old Speedos, the Triumph’s seat is comfy and the cockpit fits like a perfectly broken in pair of 501s.

Why did the bad guys in The Wild One have Harleys? I asked myself.

Surfers, movie stars, hippies and cowboys; pot growers, monks and divorced moms with Meg Ryan haircuts driving monster SUVs carrying Save The Planet stickers on the bulldozer sized bumpers all live up here. I am on my way over the hill to meet someone with a real story.

With a smile on side of his face Whitey Hughes, 82 at the time, confirmed that he knew the story. “I know all about the motorcycles in The Wild One. I was the head stuntman. Columbia came to us for this motorcycle movie because we were cowboys. Not many guys in movies rode bikes. So the studio asked the cowboys if they could learn to ride a motorcycle. Me and my brother already did. We lived in Chatsworth when it was way out in the country. Nothing for miles. You could ride from L.A. to Tucson then El Paso. Off the road.”

“What kind of bikes?” I asked.

“Triumphs. They were light. They revved way up there. too. Foot shifters and hand clutches. Suspension. Riders bikes.”

“Could Brando ride a motorcycle?”

“Marlon could ride. One of the guys. Rode a bike in New York before he came to Hollywood. Funny thing though, his double couldn’t. So he taught him. Marlon would always eat lunch with the crew. Not the big guys, just us below the line people. So one day on the way to lunch with us he puts his double on his motorcycle there in front of us all. The guy has his hands on the bars but Marlon is sitting behind him and has the controls. Brando motors over to the top of this here hill there in Burbank. By the lot. Where we shot the picture. Marlon says to us that he will now teach his double how to ride. Brando twists the gas on and that bike flies into the air and Marlon just slides off the back of that Triumph!”

“Why did Lee Marvin, the bad guy in the movie, ride a Harley?” I asked.

“He didn’t ride anything because he couldn’t ride. But he learned, got hooked on it and went racing.” said Whitey.

“On a Triumph,” I stated. “I looked that up in the book Triumph in America.”

“But on the show we just rode what turned up. Nothing special about that Harley of Marvin’s.”

“We found where Chino’s outfit came from,” I said. “But who did the wardrobe for Brandon?” There is no costume designer or wardrobe listed in the credits for the movie.”

‘’Don’t know,” said Whitey. “Marlon always wore jeans. T-shirt and a leather jacket. People in Hollywood back then called him The Slob. He invented that look in Streetcar.”

I recalled that in his autobiography Charles Mingus tells a secret – that he invented himself in a dream. But who invented Johnny? I asked myself again.

“What about Hollister?” I continued with my questions. “Was that real? Where did the Wild One story come from?”

“Wasn’t there. Can’t really remember.” Whitey said. “We did the movie in 1954. Hollister was what…1947?”

“OK…but why did Brando ride the Triumph?” I asked.

“Well, like his clothes, everything he did was always different. He just might have used the T’Bird because it was different.”

“Or just because he got it free?” I offered. “Someone told me that.”

“I know that Jimmy Dean got one free, but he wanted one because Marlon had one first,” Whitey replied. “Robert Taylor had a Speed Twin before Brando came to town.”

“But why did Johnny Strabler ride a Triumph in The Wild One?” I asked insistently. “What isthe story of that motorcycle?”

“Ever tell you how I was there when Steve McQueen started riding Triumphs?” asked Whitey.

“That,” I responded, “is another story.”

Epilogue

It is nearly nine by the clock on the bike’s dash and quite dark as I coast silently down towards the Pacific. I head south. Down near the edge of the city at Sunset Boulevard, the all night eruption of electric light the almost ten million people cause in L.A.county, explodes over the dark coastal mountains like hot whitewater rapids and cascades down into the foggy glow under the tall street lamps of the Coast Highway as it curves softly inward around Santa Monica Bay and escapes the collision on its way north out of town. All alone on the Coast Highway. Just me and the motorcycle.

I throttle down to think of what I found on this search for the secrets of dreams. My face shield fills with the honest reality of sage rising from the empty hot road. Perfumes created by the cool drifting veil of ocean breeze. I think about the road. Eternally tortured by fire, floods and betrayed by the convulsions of the moving, falling earth itself, PCH still feels loyally attached to the bike. This old friendly road carried me to other secrets before. The year before I got serious after full-time surfing. The year before college, before a real job…before kids and divorces, the road took me to the secrets of another invented dream.

I was in the T’bird daddy didn’t take away. She was drivin’. I can’t admit to what I was doing on The Coast Highway that spring break evening when the City of Newport Beach hired the Beach Boys to play free at Newport High to keep us away from surf music. I don’t think it was legal. Down the hill from the high school on the Balboa Peninsula, the rotting Rendezvous Ballroom was shaking like a trembler with too many blonde surfers who weren’t convinced the Beach Boys were the answer. The only dark-haired guy was on the stage, in a haze of eye-straining yellow light speed picking a Lebanese folk song upside down on a Stratocaster.

At my first real job later I would help invent the dream of that guitarist as a real surfer. I would help invent more dreams. These dreams wrapped in fashion, fashioning culture. Some fade, some define a generation, some define a subculture, some define you.

It was an adventure finding the secret of dreams. Like the trophy on the fender of his bike, the secret to Johnny is the real prize. The success of finding the origins of biker cool that came from the fashion of bad and power, its Prussian origins of aristocratic cool. The real story of The Wild One is the jacket. It’s enough for bikers that Brando rode a bike; the Triumph is for some significant by being there. Being under Brando, being in the Hollywood version of Hollister, which is the only one our culture knows or care of. Is it accidental cool? We won’t know. But for most what is significant is just that on it he’s a biker. And anyway, the jacket is the story. Biker is universal, but the concept of jacket isn’t. Black leather is, even more so by its Prussian lapels, officer epaulets, zippers, and a badass warrior fit.

The wet air thrown off the waves breaking in the moonlight at first point in Malibu pushes the smell of the sage in my helmet back to the hills. I pull the zipper up on my black leather jacket. Johnny Strabler lives.

THE END

“

“Had Hollister not happened, had Life magazine not written their article, had Hollywood not glorified it,

I don’t know if we would be here today.”

–Tom Bolfert of Harley-Davidson, Smithsonian Magazine

Thanks to Patrick Cook ; Mark Brady, Todd Andersen & Monika Boutwell ; Peter Jones, Whitey Hughes, Harvey Keith,Boyd Elder.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Precious Gems

Boy, do we hear some of the best “back in those days” stories around here. Take all the Alaskan personalities, combine them with Biker personalities and just roll the dice to see where they’ve been and what they’ve seen!! Pictures are always worth 1000 words so I felt like I had received a precious present from Cliffy when he shared his images from the 1954 Hollister Riot. I hope you enjoy them as much as we do – Thanks Cliff!

The Boozefighters

.

by Eric Johnson

It was 1946 when an individual named Willie Forkner crashed through a fence during a race in El Cajon, California and joined in the fun. The club he was in did not find it funny so they kicked him out.

Well Willie took it in stride and went about finding other outcast veterans who found life back in the States overwhelmingly dull. He didn't have to look long or far. Fatboy Nelson, Dink Burns, George Menker and more than a few others were ready for a change in some of the formalities of the clubs at the time.

It is said that the club was actually formed at the All American Bar, in the blue-collar town of South Gate in Los Angeles. A fitting name for a group that consisted of many Veterans of the great War, they had been there, done that so to speak and the quiet life just wasn't in them...

So “Wino” Willie Forkner joined these men together and formed "The Boozefighters" (BFMC). The group pushed the limits of their bikes and themselves, racing to extreme speeds and pushing the danger envelope. As the group's name suggests, you can be sure there was no lack of the forbidden fruits of hops, barley, and wine. This combination of speed and liquor helped the Boozefighters obtain a less than desirable reputation with the common folk.

by Eric Johnson

It was 1946 when an individual named Willie Forkner crashed through a fence during a race in El Cajon, California and joined in the fun. The club he was in did not find it funny so they kicked him out.

Well Willie took it in stride and went about finding other outcast veterans who found life back in the States overwhelmingly dull. He didn't have to look long or far. Fatboy Nelson, Dink Burns, George Menker and more than a few others were ready for a change in some of the formalities of the clubs at the time.

It is said that the club was actually formed at the All American Bar, in the blue-collar town of South Gate in Los Angeles. A fitting name for a group that consisted of many Veterans of the great War, they had been there, done that so to speak and the quiet life just wasn't in them...

So “Wino” Willie Forkner joined these men together and formed "The Boozefighters" (BFMC). The group pushed the limits of their bikes and themselves, racing to extreme speeds and pushing the danger envelope. As the group's name suggests, you can be sure there was no lack of the forbidden fruits of hops, barley, and wine. This combination of speed and liquor helped the Boozefighters obtain a less than desirable reputation with the common folk.

Just Rob, some hot chic as well as Boozefighters and the general public

Just Rob, some hot chic as well as Boozefighters and the general publicstop by the Russellville bar on one of our Poker Runs.

The media took that reputation to the next level when the BFMC attended the infamous Hollister, CA Fourth of July party of 1947. The party got out of hand when some juiced up members of the BFMC were arrested for drinking and street racing. That incident provided much of the inspiration for the film The Wild Ones, which starred Marlon Brando. In fact, Wino Willie was believed to be the inspiration for "Chino," Lee Marvin's character in the film. Together the Hollister “riot” and the film jump started the outlaw motorcycle club scene.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The POBOB MC tell it more like the media:

Hollister Riot 1947

On July 3, 1947, the festivities in Hollister began. Around 4,000 motorcyclists flooded Hollister, almost doubling the population of the small town. They came from all over California and the United States, even from as far away as Connecticut and Florida. Motorcycle Clubs in attendance included the Pissed Off Bastards of Bloomington. The town was completely unprepared for the number of people that arrived. The large attendance was unexpected since not nearly as many people had come in previous years. Initially, the motorcyclists were welcomed into the Hollister bars, as the influx of people was great for business. But soon, they started causing a problem in Hollister. The drunken motorcyclists were riding their bikes through the small streets of Hollister and consuming huge amounts of alcohol. They were fighting, damaging bars, throwing beer bottles out of windows, racing in the streets, and other drunken actions. Due to the huge attendance, there was a severe housing problem. The bikers had to sleep on sidewalks, in parks, in haystacks and on people's lawns. By the evening of July 4th, "they were virtually out of control".

This was all too much for the seven-man police force of Hollister to handle. The police tried to stop the motorcyclists' activities by threatening to use tear gas and by arresting as many drunken men as they could. Also, the bars tried in vain to stop the men from drinking by refusing to sell beer and voluntarily closing two hours ahead of time. The ruckus continued through July 5th and slowly died out at the end of the weekend as the rallies ended and the motorcyclists left town. At the end of the Fourth of July weekend and the informal riot, Hollister was littered with thousands of beer bottles and other debris and there was some minor storefront damage. About 50 people were arrested, most with misdemeanors such as public intoxication, reckless driving, and disturbing the peace. There were around 60 reported injuries, of which 3 were serious, including a broken leg and skull fracture.

P.O.B.O.B. MC Las Vegas

The club that might well be ground zero for the event has a web page here http://www.bfmc109.com/bylaws.html

and tells the story thusly:

By-Laws of the Original Founding Members, 1946

1. To become a Boozefighter a man must attend four meetings consecutively and be voted on by secret ballot by all members present and must not be opposed by three or more members.

2. Club is closed at twenty members.

3. Initiation fee is $2.00. Dues are .50 cents a week. When a member is voted in, he must pay the sum of $2.50.

4. If a member misses three meetings consecutively without a substantial explanation, he will be voted upon again.

5. Any member who is absent without a reasonable excuse from the club activities will automatically be dropped from the club.

6. If a member misses a meeting withou a reasonable excuse he will be fined $1.00

7. Officers will be elected every three months, if they are still living.

8. There will be a fine of $1.00 for any member not wearing his sweater to meetings, club activities, races, etc., without a reasonable excuse.

9. Any member leaving or being voted out of the club will either remove the lettering from his sweater, or sell it back to the club.

10. It is strictly against all club rules for any one member to bring more than one case of liquor or one keg of beer or wine to a meeting.

11. There will never be any women in any way affiliated in any way shape or form with the Boozefighters Motorycycle Club or its subsidiaries.

12. If any member of the Boozefighters, or its subsidiaries, is found guilty of crapping out on his back, having the club name where it can't be seen, or not having his sweater on when being crapped out, he will be fined $1.00

13. No member will be completely without a motorcycle for more than six months. If he is, he will be automatically dropped from the club.

You may contact us through our contact page. Or better yet, get on your motorcycle, find your local Boozefighters, and talk to them.

Hollister Riot

The Hollister Riot was an event that occurred during the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) sanctioned Gypsy Tour motorcycle rally in Hollister, California, July 3-6, 1947. In post-war America the popularity of motorcycles grew dramatically and this rise in popularity caused a problems for the rally; massive attendance.

Many more motorcyclists than expected, approximately 4,000, flooded Hollister, almost doubling the population. They came to watch the races as well as to socialize and drink. The motorcyclists came from all over California and other parts of the United States. They were independents and members of clubs. Some clubs in attendance included the Pissed Off Bastards of Bloomington, the Boozefighters, the Market Street Commandos, the 13 Rebels, the Galloping Goose, the Tulare Riders, the Top Hatters, the Yellow Jackets, and many more. Approximately ten percent of attendees were reported to be women.

Hollister was completely unprepared for the number of people that arrived. The main attraction soon transferred from the race track out on the edge of town to Main Street itself with riding, racing, burn-outs, rowdy behavior, and drinking.

The events of this weekend were later labeled as the “Hollister Riot”. It was sensationalized by the press with reports of motorcyclists "taking over the town" and "pandemonium" in Hollister. The strongest dramatization of the event was a staged photo of a drunken man sitting on a motorcycle surrounded by beer bottles. It was published in Life Magazine and brought national attention and negative opinion not only to the event, but also to “bikers” everywhere.

The “Hollister Riot” is considered the birthplace of the American Biker and is one of the contributing factors to the rise of the outlaw biker image.

Another site- with what appears to be some kewl info on the actor and director who is, in real life, also the current Boozefighters Pres.

Outside of the film business, Robert Patrick is also the current president of Chapter 101 of the Boozefighters Motorcycle Club. The Boozefighters (BFMC) is one of the oldest American working-class motorcycle clubs, formed in California, in 1946 by veterans fresh out of World World II. "Wino" Willie Forkner (d. 1997) is recognized by the club to be the founder. The BFMC were at the renowned Hollister Incident of July 4, 1947, which was immortalized by the movie The Wild One, starring Marlon Brando. Lee Marvin played the part of "Chino," which is said to have been based on Wino Willie. The Boozefighters have never been "one percenters" or an outlaw biker club. Their mottoes are, "The Original Wild Ones" and "A drinking club with a motorcycle problem."

http://www.bfmcnatl.com/

HOLLISTER RIOTThe Hollister Riot occurred during the Gypsy Tour motorcycle rally in Hollister, California from July 4 to July 6, 1947, three months before I was born. The event was sensationalized by news reports of bikers "taking over the town" and staged photos of public rowdiness.

The rally, which was sponsored by the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA), was attended by approximately 4000 people. This was several times more than had been expected, and the small town of Hollister was overwhelmed by bikers who were forced to sleep on sidewalks and in parks.

About 50 people were arrested during the event, most for public intoxication, reckless driving, and disturbing the peace. Members of the Boozefighters Motorcycle Club, in particular, were reported to be fighting and racing in the streets. There were 60 reported injuries, of which 3 were serious.

The 1953 film The Wild One (starring Marlon Brando) was inspired by the event and based on an article run in Lifemagazine which included a staged picture of a drunk man resting on a motorcycle amidst a mass of beer bottles. Representatives of the AMA, seeking to deflect the negative press surrounding the rally, stated at a press conference that "the trouble was caused by the one per cent deviant that tarnishes the public image of both motorcycles and motorcyclists." This statement led to the term "one-percenter" to describe "outlaw" bikers. The AMA now says they have no record of such a statement to the press, and call this story apocryphal. (wikipedia)

http://www.salinasramblersmc.org/History/Classic_Bike_Article.htm

The rally, which was sponsored by the American Motorcyclist Association (AMA), was attended by approximately 4000 people. This was several times more than had been expected, and the small town of Hollister was overwhelmed by bikers who were forced to sleep on sidewalks and in parks.

About 50 people were arrested during the event, most for public intoxication, reckless driving, and disturbing the peace. Members of the Boozefighters Motorcycle Club, in particular, were reported to be fighting and racing in the streets. There were 60 reported injuries, of which 3 were serious.

The 1953 film The Wild One (starring Marlon Brando) was inspired by the event and based on an article run in Lifemagazine which included a staged picture of a drunk man resting on a motorcycle amidst a mass of beer bottles. Representatives of the AMA, seeking to deflect the negative press surrounding the rally, stated at a press conference that "the trouble was caused by the one per cent deviant that tarnishes the public image of both motorcycles and motorcyclists." This statement led to the term "one-percenter" to describe "outlaw" bikers. The AMA now says they have no record of such a statement to the press, and call this story apocryphal. (wikipedia)

http://www.salinasramblersmc.org/History/Classic_Bike_Article.htm

The real "Wild Ones'

The 1947 Hollister Motorcycle Riot

A note for visitors to bikewriter.com: These interviews were conducted in late 1998. All participants were eyewitnesses to the events which came to be known as the Hollister 'motorcycle riot'. Excerpts of these interviews were published in Classic Bike, but the full transcripts are presented here, in order to fully document this important event in motorcycling history.

Summary/Lead:

On July 4 1947, 4,000 'straight-pipers' rode into Hollister. Their plan was to spend the long weekend partying and watching the races, but the partying got a little out of control. Even the local police admitted that the bikers "did more harm to themselves than they did to the town" but the press blew the story out of proportion. When the events were dramatized by Hollywood in 'The Wild One', America's image of motorcycling changed forever. Now you can read what really happened, in the words of people who were really there.

Introduction

At the end of World War II, the central California town of Hollister had a population of about 4,500. The gently rolling farmland surrounding the community was well-suited to motorcycle riding; there were facilities for scrambles, hillclimbs, and dirt-track racing at Bolado Park (about 10 miles away) and at Memorial Park, on the outskirts of town.

Through the 1930's, Hollister had been the site of popular races sanctioned by the American Motorcyclist Association, and promoted by the Salinas Scramblers (correction - Salinas Ramblers). Spectators rode in on A.M.A.-organized 'Gypsy Tours', and as attendances grew, the Memorial Day races became as important to Hollister as the livestock fair or the rodeo.

Racing was postponed after America's belated entrance into the war. When it was organized again for 1947, local merchants welcomed a major source of revenue back to the Hollister economy.

When peace broke out, many American servicemen were demobilized in California, and settled there. As soldiers, they had earned regular pay, but found little to spend it on. In sunny California, with extra money on hand, they did the same thing any Classic Bike reader would do. Then, when they were spent, they bought motorcycles with the dough left over.

The veterans formed hundreds of small motorcycle clubs with names like the 'Jackrabbits', '13 Rebels', and 'Yellow Jackets'. Members wore club sweaters; rode, drank and partied together; and organized informal motorcycle 'field meets'. There was no sense of territoriality, or inter-club rivalry.

The A.M.A. realized that the war had exposed many Americans to motorcycles; veterans came back with experiences of Harley Davidson's WA45. Back home, shortages of metals and fuels had encouraged people to ride instead of drive. Eager to keep these new riders, the A.M.A. sanctioned competitions and organized Gypsy Tours with renewed enthusiasm.

The army, however, is not a particularly good place to acquire social graces. The new motorcyclists drank harder, and were more rambunctious than the riders who had come to Hollister before the war.

Beginning Friday morning, thousands of motorcyclists poured into town. They came down from San Francisco, up from L.A. and San Diego, and from as far away as Florida and Connecticut. By evening, San Benito Street was choked with motorcycles. Eager to prevent the locals from straying into the crowd, the seven-man Hollister Police Department set up road blocks at either end of the main street.

At first, the 21(!) bars and taverns in Hollister welcomed the bikers with open arms. It was a good joke when motorcycles were ridden right into several taverns. But the bar owners quickly realized that the crowd required no extra encouragement. Taking the advice of the police, bartenders agreed to close two hours earlier than normal. A half-hearted attempt was made to stop serving beer, on the theory that the bikers probably couldn't afford hard liquor.

From late Friday afternoon to early Sunday morning, the overwhelmed Hollister police (and many bemused residents) watched the 'straight pipers' stage drunken drags; wheelie and burnout displays; and impromptu relay races right on the main street. Most of them ignored the sanctioned races going on at Memorial Park.

In total, 50-60 bikers were treated for injuries at the local hospital. About the same number were arrested. They were charged with misdemeanors: public drunkeness, disorderly conduct, and reckless driving. Most were held for only a few hours. No one was killed or raped; there was no destruction of property, no arson, or looting; in fact, no locals suffered any harm at all.

On Sunday, 40 California Highway Patrol officers arrived with a show of force and threats of tear gas. The bikers scattered, and returned to their jobs.

The San Francisco Chronicle ran breathless accounts of Hollister's wild weekend. While they didn't actually lie, the stories carried sensational headlines like "Havoc in Hollister", and "Riots... Cyclists Take Over Town". The A.M.A.'s public-relations nightmare got even worse two weeks later when Life Magazine ran a full page photo of a beefy drunkard, swaying atop a Harley, with a beer in each hand.

As time goes by, it becomes harder to separate the Hollister myths from reality. It couldn't have been too bad, because the town agreed to allow the A.M.A. and the Salinas Scramblers to promote motorcycle races again just five months later. Local bartenders welcomed the bikers (and their wallets) once more.

The community was the calm at the eye of a national storm. Hollister, which had actually experienced the 'riot', was ready to have the bikers back; meanwhile towns across the U.S. which had only read the press coverage, cancelled race meetings. Police departments also fostered the notion that roving bands of ruthless motorcycle hoodlums might descend on their towns at any moment. This worked especially well at budget time.

When Hollywood dramatized the Hollister weekend in the 1954 film The Wild One, any hope of salvaging motorcycling's image was lost. At best, it showed bikers as drunken misfits; at worst, sociopaths. The movie's only redeeming scene comes when a ride on Brando's Triumph weakens the resolve of a beautiful, but chaste, young woman. If only that were true.

Ironically, the sensational media coverage of Hollister helped to spawn truly criminal 'outlaw' bike gangs. Once the public fear of motorcyclists reached a fever pitch, bikes held irresistable appeal for genuine sociopaths. A few predators formed clubs, and were egged on by wildly-exagerated media portrayals of biker crime. By the 1960's, clubs like the Hell's Angels made Marlon Brando look like, well, Marlon Brando. The A.M.A. has been fighting a public relations rearguard action ever since.

Eyewitnesses

Bertis 'Bert' Lanning

Bert Lanning was 37 years old when the '47 Gypsy tour rode into Hollister. As a mechanic in a local garage, he had direct contact with many of the bikers involved.

"I worked in Hollister, at Bernie Sevenman's Tire Shop, right on the main street. I had motorcycles myself, a Harley '45, and a Triumph. I'm 88 now and my eyes aren't good enough to ride anymore, but I've still got a bike in my garage!

There was a mess of 'em. Back then, beer always came in bottles, and there were quite few of them broken in the streets, so the bikers were getting flat tires. They'd bring them into the shop, either to get them fixed, or they'd want to fix them themselves. Eventually it got so crowded in and around the shop that guys were fixing tires out in the street, running in and out to borrow tools. Maybe a couple of tools went missing. Anyway, my boss got nervous and told me to close up the shop. I thought that was great, because I wanted to get out there myself.

Main Street was packed, but it wasn't nearly as bad as the papers said. There was a bunch of guys up on the second floor of the hotel, throwing water balloons. I didn't see any fighting or anything like that. I enjoyed it. Some people just don't like motorcycles, I guess."

Bob Yant

Bob Yant owned an appliance store on Hollister's main street. Back then, appliances were built to last, and so was Bob: He still works at the store every day.

"In 1947, I had just bought into my Dad's electrical contracting and appliance business. We had a store right on San Benito (street). There were motorcyclists everywhere; they were sleeping in the orchards.

Our store was open that Saturday. Guys were riding up and down Main Street, doing wheelies. The street was full of bikes, and the sidewalks were crowded with local people that had come down to look. Actually, it was bad for my business; my customers couldn't get to the store. It was so slow that I left early, and let my employee lock up.

On Sunday, I went to the hospital, to visit a friend. There were a bunch of guys injured, on gurneys in the hallway, but I think they were mostly racers. There must've been about 15 of them, which was quite a sight in such a small hospital.

There was no looting or anything; I was never afraid during the weekend. You know we had a few little hassles even when the motorcyclists weren't in town. I think some guy rode a bike into 'Walt's Club' (a bar) or something, and somebody panicked. The Highway Patrol came en masse and cleared everybody out.

The day after everyone had left, near my store, there were two guys taking a photograph. They brought a bunch of empty beer bottles out of a bar, and put them all round a motorcycle, and put a guy on it. I'm sure that's how it was taken, because they wanted to get high up to take the shot, and they borrowed a ladder from me. That photo appeared on the cover of Life magazine. (Author's note: I do not have any evidence that Life ever ran the Hollister story on the cover)

Not long after that, they turned the little racetrack into a ballpark."

Catherine Dabo

Catherine Dabo and her husband owned the best hotel in Hollister. When bikers were being demonized in the media, she always defended them.

"My husband and I owned the hotel, which also had a restaurant and bar. It was the first big rally after the war. Our bar was forty feet long, and a biker rode in the door of the bar, all along the bar, and through the doors into the hotel lobby!

We were totally booked. Every room was full, and we had people sleeping in the halls, in the lobby, but they were great people; we had more trouble on some regular weekends! I was never scared; if you like people, they like you. Maybe if you try telling them what to do, then look out!

The motorcycles were parked on the streets like sardines! I couldn't believe how pretty some of them were.

I was great for our business; it gave us the money we needed to pay our debts, and our taxes. they all paid for their rooms, their food, their drinks.

They (the press) blew that up more than it was. I didn't even know anything had happened until I read the San Fransisco papers. The town was small enough that if there had been a riot anywhere, I'd have known about it! I had three young children, we just lived a few blocks away, and I was never scared for them. I think the races were on again in '51. My husband and I always stood up for the bikers; they were good people."

Gil Armas

Gil Armas still rides a 1947 Harley 'Knucklehead'. He competed in dirt track events, and later sponsored a number of speedway riders.

"Back then, I was a hod carrier; I worked for a plastering outfit in L.A.. I had a '36 Harley, and rode with the Boozefighters. We used to hang out at the 'All American' bar at Firestone and Central. Lots of motorcycle clubs hung out there, including the 13 Rebels, and the Jackrabbits.

Basically, we just went out on rides. Some of us went racing, or did field meets, where there events like relays, drags; there was an event called 'missing out' where you'd all start in a big circle, and if you got passed, you were out. At first, most of our racing was 'outlaw' races that we organized ourselves, but a few years later, a lot of us went professional, and raced in (A.M.A.-sanctioned) half miles and miles. I retired (from racing) in '53.

I just went out to Hollister for the ride. A couple of my friends were racing. My bike was all apart, and I threw it on a trailer and towed it up there; I didn't want to miss out on the fun. I ended up sleeping in the car.

We started partying. There were so many motorcycles there that the police blocked off the road. In fact, they sort of joined in. There were four of them in a jeep. We sort of had a tug-of-war, with us pushing it one way, and them pushing it the other. Tempers flared a little when somebody stole a cop's hat, but it all blew over. There was racing in the street, some stuff like that, but the cops had it under control.

Later on, the papers were telling stories like we broke a bunch of guys out of jail, but nothing like that happened at all. There were a couple of arrests, basically for drunk-and-disorderly; all we did was go down and bail them out. In fact, a few of the clubs tried to force the papers to print a retraction. They did write a retraction, but it was so small you'd never see it.

The bar owners were standing out front of the bars saying 'Bring your bike in!'. They put mine right up on the bar.

On Sunday, the cops came back with riot guns, and told us all to pack up and leave. At first, we just sat on the curb and laughed at them, because there was no riot going on, but we all left anyway.

In those days, if you rode a motorcycle, then anybody that rode a motorcycle was your buddy. We (Boozefighters) were just into throwing parties."

August 'Gus' Deserpa

I saw two guys scraping all these bottles together, that had been lying in the street. Then they positioned a motorcycle in the middle of the pile. After a while this drunk guy comes staggering out of the bar, and they got him to sit on the motorcycle, and started to take his picture.

I thought 'That isn't right', and I got around against the wall, where I'd be in the picture, thinking that they wouldn't take it if someone else was in there. But they did anyway. A few days later the papers came out and I was right there in the background.

They weren't doing anything bad, just riding up and down whooping and hollering; not really doing any harm at all."

Marylou Williams

Marylou Williams and her husband owned a drug store on Hollister's main street.

"My husband and I owned the Hollister Pharmacy, which was right next door to Johnny's Bar, on Main Street. We went upstairs in the Elks Building, to watch the goings-on in the street. I remember that the sidewalks were so crowded that we had to squeeze right along the wall of the building.

Up on the second floor of the Elks Building, they had some small balconies. They were too small to step out onto, but you could lean out and get a good view of the street. I brought my kids along; I had two daughters. They were about 8 and 4 at the time. It never occurred to me to be worried about their safety. We saw them riding up and down the street, but that was about all; when the rodeo was in town, the cowboys were as bad."

Harry Hill

Harry Hill is a retired Colonel, USAF. He was in visiting his parents in Hollister during the 1947 riots.

"I was in the Service then, but I was home for the long weekend. Hollister was a farming community back then. The population was about 4,500 or so. Now it's a bedroom community for Silicon Valley, and the population is about 20,000.

Before the war, they had had motorcycle races out at Bolado Park, about 10 miles southeast of town. I believe the big event was a 100-mile cross country race. Back then, the AMA had a thing called a Gypsy Tour; people would come from all over on motorcycles. Besides the races there were other contests: precision riding, decorating motorcycles.

I liked motorcycles; I started riding in about 1930, and at different times had both Harleys and Indians. I stopped riding when I enlisted in the Air Force, in about '41, so my bikes were old 'tank shift' types.

Back then, the race weekend wasn't necessarily the biggest thing in town, but it was as big as the rodeo, or the saddle horse show. It seems to me that there were always two or three people killed during those weekends; people racing, and riding drunk, but things changed after the war; they got a lot rowdier.

In '47, I was still on active duty. I guess I was quite a bit more disciplined than the average biker that rode in that weekend. It was such a madhouse; my parents were elderly, too, and I didn't feel it was right to leave them alone, so I stayed around the house. I sure heard it, though.

On Sunday, I took a look around. It was a mess, but there was no real evidence of any physical damage; no fires, or anything like that.

There seemed to a be alot more drinking going on when the motorcycle boys were in town, than when the cowboys were in town. When the motorcycle boys got rowdy, we used to say 'Turn the cowboys loose on 'em!'.

Years later, I started riding again. Frankly, I was worried about the image we had as motorcyclists: the Hell's Angels, the booze, the whores... (motorcycling's) reputation got real bad. And there continued to be bad publicity at places like Bass Lake, where there was a big annual biker gathering. But I rode because I loved it. My last bikes were a Kawasaki Mach III in the seventies, and a Kawasaki 1000, which I sold in 1990."

Jim Cameron

Jim Cameron is still a motorcycle racer, riding a Jeff Smith-built BSA Gold Star in vintage motocross events. "Because of my age," he laughs, "AHRMA will only let me compete in the 'Novice' class!"

"I was a Boozefighter. The Boozefighters were formed a year or so earlier. Wino Willie had been a member of the Compton Roughriders. They had gone to an AMA race, a dirt track, in San Diego. In between heats, Willie, he'd been drinking, of course, started up his bike and rode a few laps around the track, just for laughs. Eventually they got him flagged off. The Roughriders sort of kicked him out of the club for that; they felt he had embarassed them.

Willie decided that if they couldn't see the humour in that, he'd start his own club. Back then a bunch of us hung out at a bar in South L.A., called the All American. Several clubs met there: the 13 Rebels, the Yellowjackets, anyway, Willie was talking to some other guy about what to name the club, and there was an old drunk listening in. This old drunk pipes up "Why don't you call yourselves the 'Boozefighters'. Willie thought that was funny as hell, so that was the name.

The name Boozefighters was misleading, we didn't do any fighting at all. It was hard to get in; you had to come to five meetings, then there was a vote, and if you got one blackball, you were out. We wore green and white sweaters with a beer bottle on the front and 'Boozefighters' on the back.

Back then, I was 23 or 24 I guess, I had just come out of the Air Force. I'd been in the Pacific, but Willie and some of the others had been paratroopers over in Europe. They'd had it pretty rough in the war. I had an Indian Scout, and a Harley '45 that I used as a messenger.

Back then, the AMA organized these 'Gypsy Tours'. One was going up to Hollister on the Independence Day weekend. That sounded good, so a bunch of us decided to ride up there.

We left L.A. Thursday night, and rode through the night. I think my Scout only went about 55 miles an hour, so it took quite a while. I think we rode until we were exhausted, and stopped to sleep for a few hours in King City. It was about 6 a.m. when I woke up. It was pretty cold, and when the liquor store opened, I bought a bottle, which I drank to try to get warm. Then I rode on in Hollister.

It was about 8:30 a.m. on Friday morning when I arrived there. I was riding up the street, and I see this guy, another Boozefighter come out of a bar, and he yells 'Come on in!'. So I rode my bike right into the bar. The owner was there, and he didn't seem to mind at all. He could see I was already pretty drunk, so he wanted to take my keys; he didn't think I should go riding in my condition. The Indian didn't need a key to start it, but I left it there in the bar the whole weekend.

I don't think there were more than maybe 7 of us from the L.A. Boozefighters there. There were some guys from the 'Frisco Boozefighters, too. One of our guys had a '36 Cadillac. He used that to tow up our trailer. We had a trailer with maybe fifteen or sixteen bunks in it; stacked three high on both sides. Basically, we'd drink and party until we crapped out, then we'd go in there and sleep it off.

They claimed there were about 3,000 guys there. I think most of them went out to the dirt track races outside of town, but we didn't. We were having fun right there. The street was lined with motorcycles, and the cops had blocked it off. Basically, guys were just showing off; drag racing, doing power circles, seeing how many people they could put on one bike, and we were just watching and laughing.

The leader of the 'Frisco Boozefighters was a guy we called Kokomo. He was up in the second or third floor window of the hotel, where there was a telephone wire that went out across the street. He was wearing a crizy red uniform, like a circus clown, and he was standing in the window pretending like he was going to step out onto the wire, like a tightrope walker. It was funny as hell.

There were a couple of cops there, but they were playing it cool. Basically, they didn't arrest anybody unless they did something to deserve it. The one Boozefighter I can think of that got arrested was a 'Frisco guy. Some of them had come down in a Model T Ford. It was overheating, and while they were driving down the street, he was trying to piss into the radiator. Anyway, they arrested him, and Wino Willie went down to try to get him out; he was pretty drunk at the time, so they arested him, too. But they let them both out after a few hours.

Around Saturday night I started to sober up. After all, I had to ride home on Sunday. I guess I, got my bike out of the bar and headed home at about 4 p.m. on Sunday. It definitely wasn't as big a deal as the papers made it out to be."

John Lomanto

John Lomanto owned a farm a few miles from Hollister. He was an avid motorcyclist, and a well-known local racer.

"I worked with my father on our farm, which was just a few miles from Hollister. We grew walnuts, apricots, and prunes. I had a '41 Harley, and was one of the original members of the Hollister Top Hatters Motorcycle Club. In fact, the first few meetings were held in one of our barns, but later on we rented a clubhouse in downtown Hollister. We met three times month. We were a real club, with a President, a Secretary, a Treasurer, and all that. Our wives came, too. Our uniform was a yellow sweater with red sleeves.

There were a few races going on that weekend; I think there was a 1/2 mile race, and a TT. I didn't go to the races, but I rode my bike downtown.

It was pretty exciting. The main street was blocked off, and the whole town was motorcycles all over the place. Everybody had a beer in their hand; I can't say there weren't a few drunks! But there was no real fighting - none of that M

The preceding article was written by Mark E. Gardiner and appeared on a web site named Classic Bike which is no longer available on the web.

Arden Van Sycle

13 REBELS

Now for the final word on that photo that stirred up so much shit:

Friday, July 2, 2010

The Hollister Invasion: The Shot Seen 'Round The World

Over the Fourth of July weekend in 1947, the AMA Gypsy Tour rolled into the sleepy farming town of Hollister, California. By the time it rolled out, nothing would ever be the same for motorcyclists again.

There are pivotal events in American history—the Civil War, Watergate, the invasion of Iraq—on which the tide of public opinion suddenly turns, altering forever the way we perceive people and events, and polarizing those on both sides of the issue. For motorcyclists, that event is known simply as Hollister.

Depending on who you talk to, Hollister is either a watershed event in the history of motorcycling, or a long-dead horse that some motorcyclists just can’t stop beating. Whether it really turned the American public against motorcyclists, or merely served as a scapegoat for a problem that already existed long before the Gypsy Tour roared into that small California town in 1947, is a question that will never be settled for certain.

But the debate that still smolders 63 years later has been marked by both a scarcity of facts and a surplus of fancy. I had heard enough versions of the “truth” about Hollister over the years that when I was assigned to write a piece about it in 1994 for the inaugural issue of American Rider, I took to the task eagerly, and remained interested in the topic for long enough afterward to do some additional investigation.

First, some background: On the evening of Thursday, July 3, 1947, motorcyclists began arriving in Hollister for the annual Gypsy Tour, a three-day carnival of races and field events planned for the Fourth of July weekend. By the next day their numbers had swollen beyond expectations.

AMA officials said they had registered 1,500 riders and that at least that many more had arrived but not registered. Later estimates of the number of riders in the town of 4,900 varied, but the most frequently quoted figure was 4,000.

By Saturday night the celebration began spilling over into the streets. The local hospital was jammed with injured bikers, and the police arrested so many revelers for a variety of offenses that a special session of night court was convened.

About 30 California Highway Patrol officers armed with tear-gas guns were called in to supplement the overmatched Hollister police force. Two blocks of the main drag, San Benito Avenue, were cordoned off and all but ceded to the motorcyclists. A band was summoned to play for them, and they danced amid discarded beer bottles. By Sunday, with the county jail bulging with hung-over lawbreakers, the party began to run out of steam. The last of the motorcyclists left after Monday’s races, and life returned to something like normal in Hollister.

How bad was the Gypsy Tour? Did the police over-react?

The question is so subjective that it borders on pointless. Remember that many of the young men who converged on Hollister that weekend arrived with the horrors of a world war still fresh in their memories. To someone who had stormed the beach at Normandy, or huddled in a foxhole on some flyspeck of sand in the Pacific, riding a motorcycle through the doors of a restaurant was nothing to get upset about.

To some of the folks on the home front, however, who had spent the war years tilling their fields, raising their children, and praying that the chaos devouring the world would spare their community, it couldn’t have been any more terrifying if German tanks had come rolling down San Benito Avenue.

Less subjective is the question of whether, as is often claimed, the press unfairly exaggerated events. The primary source of information about that weekend was the local newspaper, theFree Lance, whose reporters were not only first on the scene, but fielded telephone calls from newspapers all across the country as word of the event spread.

In the late 1990s, back issues of the Free Lance were available on microfilm, so I ordered them up from my local library. From these reports I gleaned the essential details of the story that spread in the wake of the ill-fated Gypsy Tour.

Next I ordered microfilm back issues of prominent national newspapers such as the San Francisco Chronicle, the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Daily Tribune, and the New York Times. Not surprisingly, the farther the paper was from Hollister, the more perfunctory its accounts were. In contrast to the multiday coverage in the Free Lance and the Chronicle, the Chicago Daily Tribune gave a total of 67 lines of copy to the story, the Los Angeles Times 60, and the New York Times a mere 43, and none ran photos. The tale did not grow in the telling, as I had often heard charged, but rather shrank, and the Free Lance’s account was, for the most part, accurately retold, not grossly exaggerated, in subsequent press reports.

The locals were divided in their reaction to the “invasion” of the town. “It has always been a pleasure to come to Hollister to shop—until I came over Saturday,” wrote R.E. Stevenson of nearby Salinas in a letter to the editor of the Free Lance. “The town was overrun with lawless, drunken, filthy bands of motorcycle fiends and it was impossible for law-abiding citizens to drive on your streets…drunks slept in the gutters…What is the matter with your city trustees that they allow such disgraceful happenings?”

That earned this heated response from Mrs. Ruth Reynolds: “R.E. Stevenson, our Salinas shopper, might well pick his hometown’s skirts out of the mud before he writes any more letters to the editor….While he may have been offended by the somewhat noisy mob that cluttered up his personal shopping district, I wonder what his reactions were to the indescribable horror that roared up and down Main Street in Salinas on a Saturday night during the recent rodeo…If (motorcyclists) slept in the gutter they took an awful chance—some Salinas motorist might have run over them…It was noisy, often annoying, but was damage-free….”

Just as the furor was dying down in Hollister, a single photograph fanned it back to life. The photo showed an apparently drunk biker on a Harley, a beer bottle in each hand and many more on the ground beneath his bike. It appeared on page 31 (not on the cover, as is often claimed) of the July 21, 1947, issue of Lifemagazine, over the headline “Cyclists’ Holiday,” the subhead “He and friends terrorize a town,” and the following caption:

On the Fourth of July weekend 4,000 members of a motorcycle club roared into Hollister, California, for a three-day convention. They quickly tired of ordinary motorcycle thrills and turned to more exciting stunts. Racing their vehicles down the main street and through traffic lights, they rammed into restaurants and bars, breaking furniture and mirrors. Some rested by the curb. Others hardly paused. Police arrested many for drunkenness and indecent exposure but could not restore order. Finally, after two days, the cyclists left with a brazen explanation. “We like to show off. It’s just a lot of fun.” But Hollister’s police chief took a different view. Wailed he, “It’s just one hell of a mess.”

Life’s national distribution made sure that all of America got a good, long look at the drunk on the Harley. The photo, one of two that appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle on Monday, July 7, was taken in Hollister the previous Friday night by Chroniclephotographer Barney Peterson. With the click of a shutter, motorcycling’s worst nightmare became a reality. To many motorcyclists, that one stark, black-and-white image dealt a fatal blow to their cherished self-image.

Just as allegations of exaggeration were leveled at the press accounts of the Gypsy Tour, rumors that the photo was faked have survived to the present day. At first glance, there’s nothing in the photo that is inconsistent with the general description of the events. There were certainly motorcycles in town that weekend. Police records show numerous arrests for drunkenness. And in the aftermath, city street sweepers reported hauling away at least half a ton of broken glass, mostly from beer bottles thrown in the street.

My early attempts to authenticate the photo were stymied by the fact that Barney Peterson had died a few years before. He was well remembered by his surviving colleagues at the Chronicle. “Barney was not the type to fake a picture,” recalled Jerry Telfer, a photo assignment editor who knew Peterson. “Barney was the kind of fellow who had a very keen sense of ethics, pictorial ethics as well as word ethics.”

I then shifted the focus of my search to try to discover the identity of the drunk on the bike. Peterson took less than a dozen photos in Hollister, only two of which appeared in the Chronicle. The rest sat in the photo morgue until they were published in a book called Bikes: Motorcycles and the People Who Ride Them, by Thierry Sagnier.

In this book a second photo of the drunk appears, this time with a jacket draped over his shoulder. Across the back of the jacket, partially obscured, is a patch that reads “Tulare Raiders” and “Dave” underneath. (Oddly, some of the beer bottles scattered around the bike are in different positions in this shot; seven or eight that were on their sides are now standing upright.)

I got back in touch with the Chronicle and spoke to a man there named Gary Fong. I asked him if Peterson had written down Dave’s full name or any other information about him that might help me track him down.

Fong, who had already spoken to Jerry Telfer about it, said that he had “got back to the negative, and on the negative is the name Eddie Davenport.” Fong added, “That’s what photographers did with large-format, 4x5 negatives, they put it in ink or pencil. This one’s in ink. After the negative’s dried, and they’re ready to archive it, they usually put the subject [on it].”

If the drunk on the Harley was in fact named Eddie Davenport, it increased the likelihood that the jacket he held in one of the pictures had been borrowed from someone named Dave—although it’s interesting to note that the name Davenport contains the name Dave. A nickname, maybe?

The name Dave by itself wasn't enough to go on, so I concentrated on finding Eddie Davenport. I contacted the Tulare County Assessor’s Office and found no record of an Eddie Davenport owning property in the county. I placed an ad in the local newspaper, the Tulare Advanced Register, seeking an Eddie Davenport who had attended the 1947 Gypsy Tour in Hollister; I also placed ads in papers in several adjoining areas, and sent flyers to a dozen or so motorcycle shops in the Central Valley.

Those ads and flyers had an unexpected result. Daniel Corral, Jr., a Hollister resident and a member of the San Benito County Historical Society, saw one of them and contacted me. He, too, was researching Hollister, and was also interested in the identity and whereabouts of Dave/Eddie Davenport.